President Obama on Sunday night said that it was “clear” that Tashfeen Malik and her husband, Syed Rizwan Farook, the two alleged assailants in the San Bernardino mass shooting, had “gone down the dark path of radicalization, embracing a perverted interpretation of Islam that calls for war against America and the West.” He did not speculate as to why people journey down that path or prescribe how the United States might deter, or detour, them. But a March report from Lebanon-based Quantum Communications provides some insight.

The researchers from Quantum collected televised interviews with 49 fighters in Syria and Iraq—some in custody, some who had defected, and some who were still in the fight. They analyzed the fighters’ statements using a psycho-contextual analytical technique developed by Canadian psychologist Marisa Zavalloni to divine the motivational forces and personal characteristics of the subjects.

It is a small sample, and not random, but given the difficulty of surveying a group like ISIS, it still provides value. How much value? Michael Lumpkin, assistant defense secretary for special operations and low-intensity conflict, cited the report in his recent visit to Congress.

I showed the report to University of Maryland professor Arie W. Kruglanski, one of the principal investigators at the National Center for the Study of Terrorism and the Response to Terrorism. He responded, “The content analysis that the researchers employed is a well-respected method of gleaning information from contents of interviews. … More importantly the findings make sense to me.”

Almost all research on terrorism faces this problem of finding a truly random sample, said Paul Davis, a senior principal researcher at the Rand Corporation and a professor of policy analysis at the Pardee Rand Graduate School. “I applaud the article,” Davis said. “It is consistent with the strong finding we’ve found and continue to find, which is that motivation is very important and that motivation varies.”

The Quantum researchers grouped the fighters into nine categories, based on the reasons they gave for joining ISIS or other extremist groups. They are:

- Status seekers: Intent on improving “their social standing” these people are driven primarily by money “and a certain recognition by others around them.”

- Identity seekers: Prone to feeling isolated or alienated, these individuals “often feel like outsiders in their initial unfamiliar/unintelligible environment and seek to identify with another group.” Islam, for many of these provides “a pre-packaged transnational identity.”

- Revenge seekers: They consider themselves part of a group that is being repressed by the West or someone else.

- Redemption seekers: They joined ISIS because they believe it vindicates them, or ameliorates previous sinfulness.

- Responsibility seekers: Basically, people who have joined or support ISIS because it provides some material or financial support for their family.

- Thrill seekers: Joined ISIS for adventure.

- Ideology seekers: These want to impose their view of Islam on others.

- Justice seekers: They respond to what they perceive as injustice. “The justice seekers’ ‘raison d’être’ ceases to exist once the perceived injustice stops,” the report says.

- Death seekers: These people “have most probably suffered from a significant trauma/loss in their lives and consider death as the only way out with a reputation of martyr instead of someone who has committed suicide.”

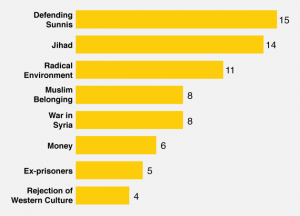

The nine potential identities are not equally represented among the survey pool.

Foreign fighters in the sample from places like the United States and Western Europe were far more likely to be facing some sort of identity crisis, a desire for a personal sense of recognition that ISIS can provide. They were also more likely to be motivated by a rejection of Western culture. A story in TheNew York Times over the summer, titled “ISIS and the Lonely Young American” detailed how ISIS sympathizers made contact with a curious and socially isolated Westerner and then manufactured a sense of community and belonging through constant online interaction (not simply one-way messaging, as some have suggested).

People in the sample who joined ISIS or similar groups from another Muslim country, however, were far more motivated by the perceived plight of the Syrian Sunnis. For this group, the report found that “assisting Muslim ‘brothers’ and fighting the Assad regime are the most common catalysts (45 percent).” They were primarily thrill and status seekers.

The fact that joining ISIS or a similar group could improve one’s immediate social status underscores how differently ISIS is perceived in the Arab world than in the West.

Sunni fighters primarily from Syria and Iraq were also motivated by money and status. “Internal fighters believe they have a mission to defend their community (duty, Jihad) but they also have personal interests (money, staying alive),” according to the report.

It quotes one jihadist: “He asked me, ‘Why don’t you join us … leave your work and consider me your financier.’”

The Quantum study is not an exploration of “lone-wolf” attacks, which is what the San Bernardino shooting appears to be. And, of course, it doesn’t answer every question about the group’s appeal, nor specifically its appeal to Malik and Farook.

Farook had family roots in Pakistan but was a native citizen of the United States. Malik was born in Pakistan and reportedly had strong ties to Saudi Arabia. This suggests that the two embarked on different “paths toward radicalism.” And much about their motivation is still a mystery, and will likely remain so.

But the interviews with “internals” expose one of the organization’s most glaring vulnerabilities, especially in the way it recruits and deals with individuals on its home turf in Iraq and Syria. The fighters identified money as a significant motivator, as significant as jihad itself. This suggests that reducing ISIS’s ability to raise funds will decrease its allure. The group also identified the perceived persecution of Sunnis as a rallying cause. This suggests that Iraqi Security Forces who are Sunni, or Sunni rebels in Syria, could peel away at the group’s recruitment base in those areas.

It was an overt announcement that followed a quieter step in that direction.

In October, Defense Secretary Ashton Carter announced that he had placed Army Lieutenant General Sean MacFarland in charge of the coalition fighting ISIS in Iraq and Syria. MacFarland is credited with orchestrating the so-called “Sunni Awakening,” and establishing partnerships with Sunni tribal sheiks, a program that eventually produced 200 such partnerships.

In terms of fighting ISIS messaging, the president announced, “We are cooperating with Muslim-majority countries, and with our Muslim communities here at home, to counter the vicious ideology that ISIL promotes online.”

The administration has been under pressure to do more in this area, and the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act, or NDAA, provides some additional authority to the Defense Department. It states, “The Secretary of Defense should develop creative and agile concepts, technologies, and strategies across all available media to most effectively reach target audiences, to counter and degrade the ability of adversaries and potential adversaries to persuade, inspire, and recruit inside areas of hostilities or in other areas in direct support of the objectives of commanders.”

The military is expected to rely heavily on outside contractors in the effort, due to what Special Operations Command commander General Joseph L. Votel described as a “lack of organic capability” to counter ISIS’s online messaging.

Is the attempt to categorize different militants on the basis of motivation using social-psychological techniques—even legitimate? The results are more qualitative than quantitative. The question of whether or not psychology, or the social sciences in general, is as reliable or credible as natural sciences such as chemistry that produce repeatable results is not new. But it is science. The Quantum report is in keeping with the conventions and practices contemporary of social-science research according to two leaders in the field.

Marketers have used social psychology for decades to make billion-dollar decisions about how to sell products and to understand how different external and internal factors motivate people to take action. That’s exactly what the Pentagon is charged with doing, now. Stopping the spread of radicalism via social media is, fundamentally, a challenge of marketing. So it stands to reason that marketing should have some place in that fight.

The draw of the Islamic State is not as irresistible as today’s headlines suggest, but that doesn’t mean that the United States is yet able to reach the group’s target audiences with something more appealing.

theatlantic.com