Its hackers have tried to penetrate computers that regulate the nation’s electricity grid, U.S. officials say.

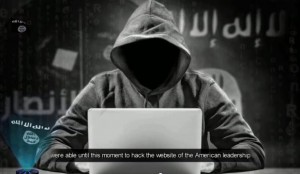

The Islamic State is seeking the ability to launch cyberattacks against U.S. government and civilian targets in a potentially dangerous expansion of the terror group’s Internet campaign.

Though crippling attacks for now remain beyond the reach of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, also known as ISIL, its hackers have tried to penetrate computers that regulate the nation’s electricity grid, U.S. officials say. On shadowy Internet forums, ISIL sympathizers post photos and videos of airplane cockpits and discuss wanting to crash passenger jets by hacking into on-board electronics. Fellow extremists debate triggering a lethal radiation release by sending rogue commands to nuclear power plants, according to the New York-based threat intelligence firm Flashpoint.

To date, a lack of world-class expertise has limited ISIL and its supporters to defacing websites, including that of an organization for U.S. military spouses, and pranks such as commandeering the Twitter feed of the U.S. military command directing operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. In September, James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, told Congress that the danger of a catastrophic attack from any cyber adversary was “remote.”

But Islamic State adherents have made no secret of their desire to acquire lethal capabilities, says Alex Kassirer, a Flashpoint terrorism analyst, who monitors conversations on extremist forums.

“The capability’s not there and that’s why we’re seeing these low-level attacks of opportunity,” Kassirer said. “But that’s not to say it’s going to be that way going forward. They’re undoubtedly working on cultivating those skills.”

The added danger of ISIL’s burgeoning cyber capabilities is that the terrorist group doesn’t operate according to the same rules as even the most reckless nations. Deterrent strategies that keep even virulently anti-U.S. states such as North Korea at bay are unlikely to succeed with the Islamic State.

“You’re dealing with a group that’s more unconstrained than [nation] states, China, Iran and so forth … that’s launched extraordinary terror attacks, beheadings, that sort of thing,” said Dick Newton, a retired three-star Air Force general who directed cyber policy for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “They are willing to create havoc.”

U.S. vulnerability to cyberattacks is well known. Nearly 22 million individual records were stolen when hackers believed to be from China penetrated the government’s central personnel office computers. American companies’ annual losses to cyber thieves total 0.64 percent of gross domestic product, or roughly $115 billion, according to a 2014 Center for Strategic and International Studies report.

The U.S. government spends more than $5 billion annually on cyberdefense with responsibility divided among the departments of Defense and Homeland Security, the National Security Agency and the FBI. U.S. companies, primarily responsible for their own protection, spend a multiple of that figure.

While ISIL — under growing military pressure in its would-be Middle Eastern caliphate — has mainly put its efforts into inspiring scattered shootings and bombings rather than organizing mass casualty attacks, cyberspace could become a more active front in the war on terror.

“Destructive malware is a bomb. Terrorists want bombs,” FBI Director James Comey said in May, referring to malicious software that disables or wrecks computer networks.

ISIL also recognizes that it might be easier to strike at the U.S. from afar using digital weapons than to infiltrate terrorists across the border. “I see them already starting to explore things that are concerning, critical infrastructure, things like that,” Comey said of the group. “The logic of it tells me it’s coming, and so of course I’m worried about it.”

The concern is not limited to the U.S. government. Four days after ISIL terrorists killed 130 people in Paris, Britain’s top Treasury official warned that the terror group is dedicated to striking critical infrastructure, such as the financial system or power grid.

“We know they want it and are doing their best to build it,” said George Osborne, the U.K. chancellor of the exchequer.

The previous month, Caitlin Durkovich, U.S. assistant secretary of homeland security for infrastructure protection, told an electric industry conference that Islamic State terrorists have launched cyber attacks on the grid.

To date, ISIL’s cyber achievements have been limited, although the U.S. charged a Kosovo native in October with hacking into a U.S. database and stealing personal information on more than 1,350 military and government personnel. The suspect, Ardit Ferizi, later passed the data to Junaid Hussain, a member of the self-proclaimed Islamic State Hacking Division who was reportedly killed by an airstrike in Syria in August, authorities said. The information Ferizi pilfered included U.S. personnel’s email addresses, passwords, locations and phone numbers, according to the Justice Department.

In the first case of its kind, the department charged Ferizi with providing material support to a terrorist organization, computer hacking and identity theft violations. He was living in Malaysia at the time of his arrest and, if convicted, faces 35 years in prison.

Compared with earlier terrorist generations, ISIL has demonstrated an appeal to young, tech-savvy individuals far from the battlefields of Iraq and Syria, Kassirer said.

“Al Qaeda’s media apparatus was a van driving around Yemen passing out videos,” she said. “ISIS has really revolutionized how they use the tech sector and their recruits tend to be younger individuals who grew up in the tech age.”

The group has also shown a sophisticated understanding of ways to shield its communications from eavesdropping intelligence agencies. Flashpoint earlier this month reported on a detailed manual released by an ISIL supporter urging members to use the popular encrypted chat system Signal. The manual even describes how to employ a fake phone number to set up a Signal account to avoid revealing personal information.

That’s a far cry from Al Qaeda, which communicated via couriers to escape surveillance, she said.

Experts have traditionally discounted the risk of cyberterrorism, saying terrorists prefer the greater chaos and bloodshed of physical attack. The technical skill required to execute a major cyberattack also was judged beyond any but a few nation-states.

Even Pakistan’s Lashkar-e-Taiba, one of the most technically sophisticated terrorist groups, which claimed responsibility for the 2008 Mumbai attacks, has focused mainly on using its cyber expertise to safeguard its communications, said Tricia Bacon, a former State Department counterterrorism official who is now an assistant professor at American University in Washington, D.C.

Lashkar-e-Taiba recruits heavily from top Pakistani universities and often pays more than local tech companies, giving the group its pick of tech talent, she said. The group was founded by engineering instructors at a university in Lahore and retains ties to major political parties and the Pakistani military.

“Lashkar has an overt presence all over Pakistan,” Bacon said, including offices at universities. “The recruitment need not be surreptitious because the group is part of the political elite.”

The absence to date of cyberattacks attributed to the group may be because the potential damage would not be sufficiently visible.

“One aspect of terrorism is theater,” she said. “Maybe no one’s come up with a sufficiently creative or ingenious plot yet that uses those capabilities. A basic malware attack rarely has that.”

But ISIL’s recent embrace of the most convenient attack, rather than the largest or most gruesome one, may have changed the traditional calculus. In January, the group’s Cyber Caliphate hacking unit seized control of U.S. Central Command’s Twitter and YouTube feeds, posting propaganda videos and contact information for top military officials before being expelled. In November, the same hackers seized more than 50,000 Twitter accounts and used them to spread propaganda.

Though theatrical, these hacks did not produce physical damage and required little expertise. Seizing control of the Centcom Twitter feed, for example, was likely accomplished with a simple phishing attack — infecting the command’s network via a virus disguised in a legitimate email.

Organizational Twitter accounts are typically protected with a single password held by numerous people, any one of whom might be tricked into giving it up. Because Twitter is so popular, hackers regularly share tricks to compromise it on forums.

If a group doesn’t have in-house hacking talent, it can also buy those skills on the Dark Web. In those nonpublic Internet badlands, populated by child pornographers and drug traffickers, hackers offer to use zombie computers to swamp a network with traffic.

The complex computer systems that run critical infrastructure, such as the energy grid, are more distinctive and difficult to compromise. The list of destructive cyberattacks against such targets is extremely limited. It includes the Stuxnet attack against the Iranian nuclear program, widely attributed to the U.S. and Israel, and the 2012 strike against the Saudi state oil company Saudi Aramco, believed to be the work of Iran.

Ferizi, the Malaysia-based ISIL sympathizer who hacked into a U.S. company’s database, didn’t demonstrate much skill. The information he collected on 1,351 U.S. government and military personnel was so innocuous that most experts believe it originated on the Internet.

Terrorists might pair a cyberstrike with a traditional attack to amp up the confusion or death toll, Bacon suggested. If terrorists overwhelmed the communication networks used by emergency responders, for example, that could magnify the damage of a physical attack. Attacking broadcast facilities might increase the public’s panic.

Still, ISIL for now is likely to stick to its traditional tools, guns and explosives, analysts said.

“As far as getting attention, there’s still going to be, in the minds of most terrorist groups, an inherent advantage in things that make loud noises and flashes and kill a lot of people as opposed to digital systems going down,” said Paul Pillar, a Georgetown University terrorism expert and former CIA analyst. “The speculation about exotic terrorist techniques, especially in the cyber arena, has outrun what groups are actually doing.”