Back in the 1990s something happened in central Bosnia-Herzegovina that inspired people to this day and helps explain why that country now has more men fighting in Syria and Iraq (over 300), as a proportion of its population, than most in Europe.

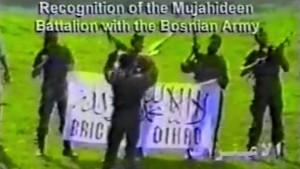

The formation of a “Mujahideen Battalion” in 1992, composed mainly of Arab volunteers in central Bosnia, was a landmark. Today the dynamic of jihad has been reversed and it is Bosnians who are travelling to Arab lands.

“There is a war between the West and Islam,” says Aimen Dean, who, as a young Saudi Arabian volunteer, travelled to fight in central Bosnia in 1994. “Bosnia gave the modern jihadist movement that narrative. It is the cradle.”

UN firefight

Conventional wisdom holds that it was the fight against the Soviet Union’s occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s that created the modern notion of jihad or “holy war”. Aimen Dean’s point is that the West and the Salafists (or adherents to a strict form of Islam going back to observance in the Middle Ages) were on the same side in Afghanistan, but became enemies in Bosnia.

At first, in 1992, it was just a few dozen militants who went to defend their co-religionists in Bosnia, as Serbian paramilitaries drove them from their homes in the west and east of the country. But it was in early 1993, when it became a three-way fight against Catholic Croatians as well as the Serbs, that the Mujahideen Battalion swelled to the hundreds and started to hunt non-believers more actively.

After Croatian militias massacred around 120 Bosnians in Ahmici in April 1993, the Mujahideen were involved in numerous reprisals. At Guca Gora monastery two months later, they drove out nearly 200 Croatians, who were evacuated by British United Nations troops. They then entered the chapel, desecrating its religious art, and filmed themselves doing it.

British troops fought the Mujahideen Battalion at Guca Gora and elsewhere in the summer of 1993 – the opening shots of that army’s fight against jihadism. Vaughan Kent-Payne, then a major commanding a company of British troops involved in those battles, says the foreign fighters were “way more aggressive” than local Bosnian troops, frequently opening fire on the UN’s white-painted vehicles.

In the nearby town of Travnik, that had been almost equally Muslim, Croatian and Serb before the war, the foreigners helped drive out thousands, and tried to impose Sharia law on those who remained. They were also involved in kidnapping local Christians, and beheaded one, Dragan Popovic, forcing other captives to kiss his severed head.

‘They did Bosnia a disservice’

The Popovic case eventually went to court, so the facts have been well established. But the Mujahideen Battalion was also suspected in many others including the kidnap and murder of aid workers as well as the execution of 20 Croatian prisoners.

The foreigners never amounted to more than one per cent of the fighting force at the disposal of the Sarajevo government, despite the frequent claims of the Serb and Croatian media to have spotted Islamic fanatics from abroad just about everywhere. From an early stage the Mujahideen also started recruiting Bosnians and, by 1995, in the final months of the war, the incorporation of several hundred local men allowed the outfit to be expanded into the Mujahideen Brigade, around 1,500 strong.

By the summer of 1993, the Sarajevo government was starting to wake up to the potentially toxic effect of these jihadists on their image as a multi-ethnic, secular republic. So, in an attempt to control it, the battalion was placed under the command of III Corps, the Bosnian Army formation headquartered in the central city of Zenica.

Its commander at the time, Brigadier General Enver Hadzihasanovic, ended up facing a war crimes trial in the Hague on charges of overall responsibility for some of the Mujahideen’s behaviour, including the Travnik kidnappings. In the end, the prosecution dropped those charges, but the general served two years, having been found guilty of having (Bosnian) troops under him who had abused prisoners.

From the outset, the general had felt the Mujahideen were a dubious military asset, and wrote a secret message to army chiefs in 1993, saying: “My opinion is that behind [the Mujahideen] there are some high-ranking politicians and religious leaders.” Reflecting now on the jihadists’ participation in the war he adds, “they didn’t help Bosnia at all, on the contrary, I think they did Bosnia a disservice.”

However, as the general’s 1993 memo implied, there were some leaders, including Alija Izetbegovic, Bosnia’s President at the time, who were happy to welcome the foreign fighters, partly as a way of keeping wealthy Arab donors sweet.

Recruiting ban

When the war ended, under the Dayton Peace Accord, all foreign fighters had to leave, and they were duly ordered out in 1996. Remembering that day, Aimen Dean says there were high emotions, shouting and tears at the Mujahideen base: “And the reason is because everyone was there hoping to die as a martyr. Now that chance was taken from them.”

Hundreds of Mujahideen went from Bosnia to Chechnya, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Among their alumni were two of the 9/11 hijackers, the murderer of American hostage Daniel Pearl and numerous other al-Qaeda cadres.

More than 300 of the foreigners remained in Bosnia, buried in its soil, a testimony to the heavy casualties taken by the unit. A few dozen Arabs who had met local women or were fearful of going home also managed to stay, by taking Bosnian citizenship.

Today also there are suggestions in Sarajevo that the SDA – the late President Izetbegovic’s party – is not taking a tough enough line against foreign fighters. Only this time they are the hundreds of Bosnians who are choosing to fight in Iraq and Syria. There is “a recalcitrance from more radical elements of the SDA” about condemning those who go to the Middle East to fight, says one Sarajevo diplomat.

In fairness, the Sarajevo government has taken action to ban recruiting for foreign wars (in the name of any religion or cause) and has mounted numerous raids to disrupt extremist networks and arrest those who have returned from fighting in the Middle East.

However, its critics note that for years it turned a blind eye to those Arab Mujahideen who remained in Bosnia but continued to agitate, and has allowed several communities of home-grown Bosnian Salafists to emerge in recent years.

Among those who link what is happening now with the 1990s are Fikret Hadzic, who has been charged with fighting for the so-called Islamic State in Syria. He met our BBC team but said that legal restrictions prevented him giving an on-camera interview, however he was happy to be quoted in print.

Abdic had joined the Mujahideen unit in 1994. For years after the war he worked as a driver and mechanic before deciding he needed to join the fight against “the Assad Shia regime” in Syria. While he insisted he was not a member of IS, and disapproved of its methods, Hadzic told us that before returning from Syria last year he had met some Bosnian members of the organisation who appeared in an IS video that was released this June.

Other Bosnians who served with that unit back in the war include the leader of an important Salafist mosque in Sarajevo, and Bilal Bosnic, who is in detention awaiting trial. Bosnic is charged with recruiting fighters for the Islamic State group.

With IS now trying to start a “new front for the Caliphate” in the Balkans, there are many who worry that Bosnia is vulnerable because it remains so weak and fragmented, even two decades after its war ended.